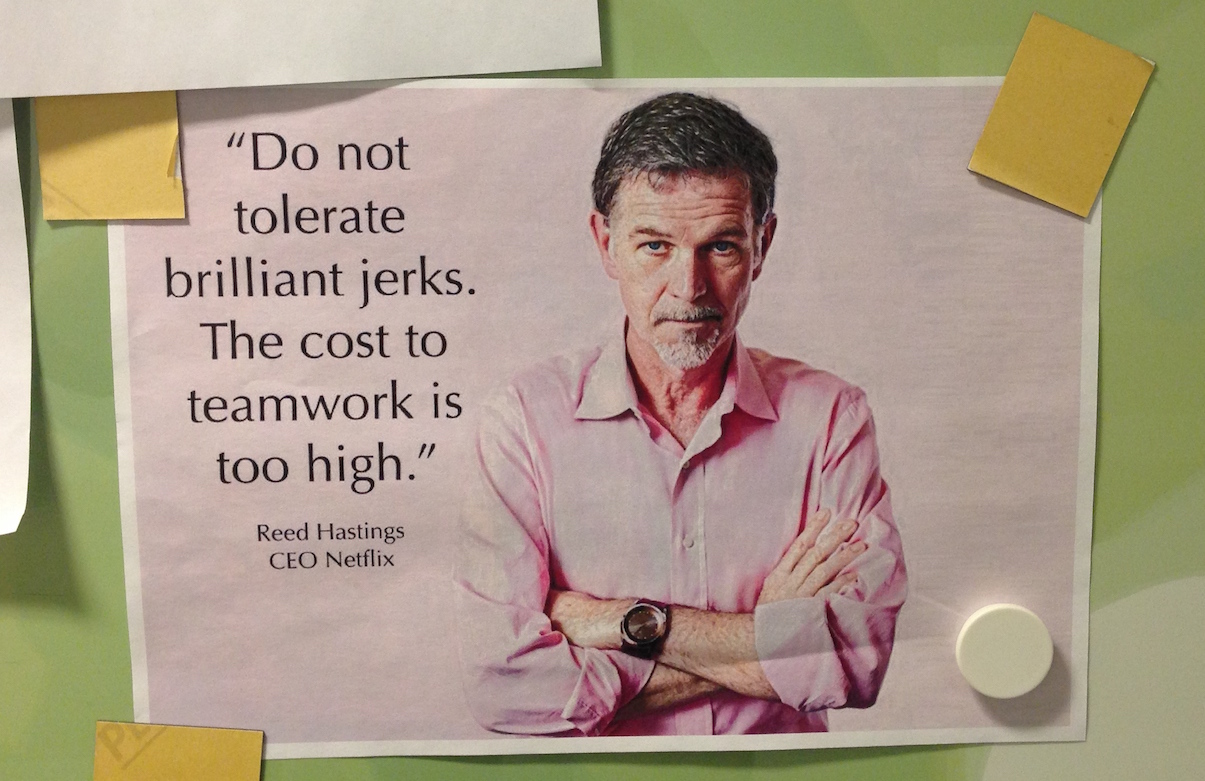

Many of us have worked with them: the engineering jerk who is brilliant at what they do, but treats others like trash. Some companies have a policy not to hire them (e.g., Netflix's "No Brilliant Jerks", which was one of the many reasons I joined the company). There's also the "No Asshole Rule", popularized by a bestselling book of this title, which provides the following test:

- 1. After encountering the person, do people feel oppressed, humiliated or otherwise worse about themselves?

2. Does the person target people who are less powerful than him/her?

Here's a test for you or your company: Would you tolerate a brilliant engineer who is also an asshole? (Or the more company-polite version: Would you tolerate a brilliant jerk?)

There are numerous articles and opinions on the topic, including Brilliant Jerks Cost More Than They Are Worth, and It's Better to Avoid a Toxic Employee than Hire a Superstar. My colleague Justin Becker is also giving a talk at QConSF 2017 on the topic: Am I a Brilliant Jerk?.

It may help to clarify that "brilliant jerk" can mean different things to different people. To illustrate, I'll describe two types of brilliant jerks: the selfless and the selfish, and their behavior in detail. I'll then describe the damage caused by these jerks, and ways to deal with them.

The following are fictional characters. These are not two actual engineers, but are collections of related traits to help examine this behavior beyond the simple "no asshole rule." These are engineers who by default act like jerks, not engineers who sometimes act that way.

Fictional Alice, the selfless brilliant jerk

Alice is a brilliant engineer. Alice cares about the company.

She is direct and honest. If she believes that an unpopular position is right for the company, Alice does not hesitate to voice it. She will even browbeat others to make her point, often coming across as mean-spirited. Alice would point out that she wasn't being mean, she was just stating what is right, and that being mean shouldn't hurt the company anyway. She has little empathy for the feelings of others, and sees little business value in having it.

Alice is great at working individually on hard engineering problems. She gets along fine with her immediate team and manager, who understand her personality. She doesn't get on well with others whom she only meets occasionally. Outside of her team, Alice is known as a jerk, and people try to avoid working with her.

Alice is great at fixing hard bugs, writing test suites, doing code merges, and other unglamorous work. If the company needs it done, she's happy to do it, and doesn't care much whether it furthers her own career.

While selfless jerks can be a net positive for the company, they can become more effective if they learn that being kind results in greater productivity. This topic was covered in the Be Kind post by boz. Different companies may have different attitudes towards Alice, whether to tolerate her behavior or not (most reviewers of this post said "no," one said "it's a grey area"). Startups may tolerate Alice, for example, since the company is so small that everyone knows Alice and understands her personality.

But I've described selfless jerks primarily for contrast with selfish jerks.

Fictional Bob, the selfish brilliant jerk

Bob is a brilliant engineer. Bob cares about Bob.

He is selfish, lacks empathy, and has delusions of grandeur. He believes that any behavior is justified that benefits himself, including abusing and exploiting others, for which he shows no guilt or remorse. He can be charming and charismatic to get his way, causing people to ignore or excuse his bad behavior.

Below is a list of attributes that describe Bob, an extreme example of a brilliant engineering jerk. Not every brilliant jerk exhibits all of these behaviors, but I've seen each and every one of them firsthand.

Bob interrupts others, and ignores their opinions. He believes that he is the most important person in the room, and has no interest in what others have to say, frequently interrupting them. He can monopolize conversations with long, exaggerated stories that flatter himself. Less-assertive engineers are effectively silenced, even if their opinions on the topic are the most valuable.

Bob only does work that benefits himself. He can work well on hard engineering problems, but only works on those he enjoys, or that help his career or promote his own earlier work. He creates new projects and immediately claims credit, but leaves the dirty work of finishing them to others, and avoids responsibility if they fail. He is brilliant at convincing the company to let him do what he wants, even when that ignores market demand or his own past performance. He never seriously mentors or trains other staff – he does not see that as useful to his own career.

Bob bullies, humiliates, and oppresses individuals. With non-technical people, he wins arguments by bamboozling them with irrelevant technical detail, making them feel dumb. With junior technical people, Bob likes to ridicule their ideas, letting everyone know how stupid they are, and how much smarter he is. When his technical specialties are needed, he makes people beg and grovel for his help, as another way to humiliate them. When others make mistakes, he enjoys shaming and mocking them with biting sarcasm and witty insults. He uses similar rhetoric in arguments, where he must always win, no matter the cost.

Bob engages in displays of dominance in front of groups. Bob likes to show everyone how important he is by how much he can get away with, including sheer rudeness. He is late to meetings (on purpose), puts his feet up on the table, then looks at his phone or laptop while ignoring everyone around him. He sometimes makes obscene remarks in the office, bragging: "If anyone else said that, they'd be fired!". He also insists on having a better laptop/desktop/monitor than everyone else, to display his status.

Bob tries to assert authority over all areas of the company, including those where he has no expertise at all. Areas he cannot control, he denigrates: E.g., as an engineer, he will claim that marketing is stupid, useless, unnecessary, and that "anyone could do it."

Bob is negative. He trash-talks other technologies, companies, and people behind their backs, always finding something negative to say. He elevates his own status by slamming other people. He also attacks technologies that either don't leverage his own prior work, or don't conform to his own beliefs. Other engineers avoid new technologies, for fear of damaging ridicule from Bob.

Bob manipulates and misleads. Sometimes he misleads subtly, by presenting facts that are literally true in a way that is intentionally misleading. At other times he will simply lie, and do it with such confidence and assertiveness that he is almost always believed. He states his own preferences and opinions as facts.

Bob uses physical intimidation. Bob glares at those he doesn't like, and may invade people's personal space. He may also use violent gestures such as slamming fists on desks.

A string of good employees have quit because of Bob. Some engineers become fed up with Bob and quit. Talented engineers are driven out by Bob on purpose, to eliminate threats to his own status. Bob demonizes those who left, attributing past failures to them, and their successes to others who stayed, especially himself. In this way, he convinces management that losing those staff was good for the company, and stops them from realizing that the real problem is Bob. Some who have left, if asked, will cite other reasons for quitting, hoping to avoid becoming victims of Bob's smear campaigns.

Bob gives great talks – about himself. Because he is a brilliant engineer and a great public orator, he is a popular speaker at technical events. In talks, he narrates self-enhancing stories and rewrites history to flatter himself, taking credit for other people's work – if not blatantly, then tacitly or by implication. He has a group of spellbound followers outside of the company who hero-worship and idolize him, and would love to work with him. He is well liked from afar.

Bob exploits junior engineers: Bob finds junior engineers who admire his brilliance, and encourages them to do work that elevates Bob's ideas and projects, reflecting glory back onto Bob. They become so invested in helping Bob's career growth that they have none of their own.

Bob is a negative role model. Bob can drag down the workplace or community by becoming a negative role model and having others imitate his behavior. Those who admire Bob become negative, bully others, and engage in similar personal attacks, hoping for his approval and to become Bob themselves. Others simply use Bob to excuse their own pre-existing bad behavior: If Bob can do it, so can I.

Some of Bob's coworkers become accomplices, and gaslight his abuse. They were there when he attacked and humiliated others, and they did nothing – or laughed along, encouraging Bob to continue. Bob likes to surround himself with such enablers. They may be otherwise reasonable people who have yet to understand that what they are witnessing is abuse. They may publicly defend Bob and deny that abuse happened, or minimize it, gaslighting Bob's victims ("everyone's a jerk sometimes").

Bob refuses to change. Bob knows that his behavior hurts people, but "that's their problem."

It bears repeating: I have seen each of these behaviors firsthand, from multiple brilliant jerks. Bob is an extreme fictional case who exhibits all of these behaviors. One particular person may exhibit only some, without necessarily being a jerk. But, if you recognize many of these traits in a colleague – or in yourself – then, yes, you're probably dealing with a major-league jerk.

Some reviewers of this post have said that Bob seems unbelievable: No one could be anywhere near that bad! They are fortunate not to have experienced a Bob, which is the lesson here. Your understanding of a "brilliant jerk" may differ from that of someone who has actually worked with a Bob, or another severe type of jerk.

The problems caused by brilliant jerks

Problems caused by Alice, the selfless jerk, may include:

- Alice hurts or offends some employees with her attitude.

- Alice causes her team and manager to spend energy mending fences with others.

- Alice's projects may be less successful, as others avoid working with her.

- Alice discourages others from asking her questions, so her technical expertise is often wasted.

But Bob, the selfish jerk, can cause these additional problems:

- Bob silences many technical opinions, lowering the company's technical IQ.

- Bob creates extra work for others who must fix his abandoned projects.

- Bob demoralizes many staff, which hurts productivity.

- Bob causes stress-related psychological and physical illness in his victims.

- Bob causes some staff to occasionally skip work: increasing absenteeism.

- Bob drives staff to quit, who will never come back.

- Bob may strengthen the company's competition, who hire those who quit.

- Bob makes it difficult to hire other good staff (word gets around).

- Bob discourages customers and investors (word gets around).

- Other staff devise processes to work around Bob, reducing the company's efficiency.

- Other staff may sabotage Bob's work, which sabotages the company.

- Bob inspires other staff to imitate his behavior, multiplying the problem.

- Bob creates a hostile workplace environment: an invitation to lawsuits.

Chapter 2 in "The No Asshole Rule" covers more details (although for general staff, not just engineers), and has instructions for calculating your TCA: the Total Cost of Assholes for your organization.

Dealing with brilliant jerks

There are two parts to this: helping the victims and staff who witness the behavior, and dealing with the jerks themselves. Both are big topics that I'll discuss here only briefly.

At some companies, no one is telling Alice or Bob that their behavior is inappropriate. Everyone sees the bad behavior, but thinks it must be tolerated because Alice and Bob are so brilliant and valuable. Wrong! One important step a company can take is to explicitly adopt a "no brilliant jerks" policy. Netflix has such a policy as part of the culture slide deck, now a memo, which reads:

On a dream team, there are no “brilliant jerks.” The cost to teamwork is just too high. Our view is that brilliant people are also capable of decent human interactions, and we insist upon that. When highly capable people work together in a collaborative context, they inspire each other to be more creative, more productive and ultimately more successful as a team than they could be as a collection of individuals.

– Netflix culture memo

This policy isn't some useless feel-good text from a nameless source: it was originally published on CEO Reed Hastings' slideshare account. To be effective, such a policy for your company may also need to come from your CEO. All Netflix candidates are told to read the culture deck (memo) when interviewing, and are told that, yes, we take it seriously. While this helps people realize that jerks should not be tolerated, it doesn't necessarily stop jerks from being hired in the first place: Bob is brilliant and charismatic and would probably pass the interview. However, he would then find himself at a company where his colleagues recognize his bad behavior as unacceptable, and are empowered to speak up about it.

In over three years at Netflix, I've worked with zero brilliant jerks. The "no brilliant jerks" policy works, and it's been great. If we hired any in that time, they either changed their ways or left the company before I could interact with them.

Some brilliant jerks can mend their ways: Alice might be motivated to change if she can be made to understand that her behavior is hurting the company, which she cares about. She should be encouraged to exercise empathy, and to leave others feeling positive and motivated to work harder, rather than demotivated. My colleague, Justin Becker, explores this in detail in his QCon talk, including the topic of emotional intelligence (EQ). In the next section I'll share an example.

As for Bob: he should be told that his behavior hurts people and the company, and given the opportunity to change – but the reality is that he probably doesn't care. He firmly believes that "nice guys finish last," and, so far, being a jerk has worked well for him. His managers have the power to change that equation, because they control things that Bob wants: they allow him to work on his pet projects and to speak at events, they give him promotions and bonuses, and ultimately they let him keep his job.

"I'd rather have a hole in my organization than an asshole."

– Fred Wilson, Velocity NY 2013 keynote.

As a colleague/victim/witness, you should report Bob's behavior to management, but you probably shouldn't ask them outright to fire Bob (among other reasons, what if someday you were thought to be a Bob?). Give management information, but let them decide how to act. Actually firing a brilliant jerk is a complicated topic for a separate post, ideally written by a manager who has dealt with this. There's usually a process to follow, which unfortunately Bob may exploit to his advantage, showing improvement when needed to keep his job, but then reverting back to his bad old ways. He may also have convinced management that his technical skills and fame are so important that the company would fail without him. This isn't true, but fear may cause management to hesitate.

For management to deal effectively with Bob, they must themselves be convinced that his behavior should not be tolerated, regardless of his brilliance. For some companies, that will require truly understanding the damage that Bob causes (listed above), to justify taking action. For companies like Netflix with an explicit "no brilliant jerks" policy, it's much easier for management to take action, as they don't need to convince anyone that jerks are a problem: that's already covered in company policy.

Regular one-on-one meetings with staff, and scheduled skip-level meetings, should also help inform management about the damage jerks are causing. Netflix does this well: I have scheduled one-on-one meetings with my manager once every two weeks, their manager once a month, and their manager at least once a year. That's three levels of management I talk directly and in private with, without even having to ask for a meeting. We're also encouraged to give other employees direct and honest feedback, intervene if we see harassment, and escalate up to and including the CEO.

As for public speaking: Bob draws power from being a public face of the company. Speaking events should be shared among staff who want to speak, and training can be made available to improve their skills (various companies offer this), so that Bob isn't the only good speaker. Conference organizers can also adopt a "no brilliant jerks" policy (some already do), and attendees can avoid conferences that host known jerks. If Alice needs to learn empathy, Bob needs to learn both empathy and to stop being selfish, and sharing public speaking or other rewarding projects is an example of the latter.

When I acted like a jerk

Many people sometimes act like Alice, and it can be easy to talk them out of it (Alice herself is harder, since it's her by-default behavior). I'll explain this with a story, this time of a moment when I acted like a jerk.

Early in my career, an engineer at my company made a big mistake in my area of expertise, and sent an email that dodged responsibility and showed no path to fix it. I was furious and phoned the engineer: my intent was to make him realize that he'd made a big mistake, and put him on the right path. I was blunt, and told him off. I didn't enjoying doing so, but I felt I was doing a Good Thing for the company, and fixing a problem.

A week later, his manager phoned me unexpectedly. He told me that he was aware of my phone call, and didn't think I was technically wrong, but did I know that the engineer has been demotivated and unproductive since I talked to him, and was it my intent to make his staff unproductive? No, of course not. The manager continued: do you think you could have told my engineer what you needed to, in a way that left them feeling positive and motivated to fix it? Sure, I probably can. Good. Always do that in the future, please. I did.

The phone call lasted less than two minutes, and was immediately effective. I suspect the manager had done this before. Notice that he did not accuse me of being a jerk, rather, he posed two questions, which were basically: 1) are you intending to hurt the company?, and 2) are you able to act decently? There's only really one right answer to those questions. If he had just said "you are a jerk" I may have just replied "no, I'm not", but by asking questions instead, it put the onus on me to think about the answer, and triggered a moment of self reflection.

Additional topics

There are some additional topics I have not covered in detail here, but should mention:

- What about jerks in open source communities? A good reference for this is the no more rock stars post, where the rock star described is pretty much Bob. See that post for the section: How do we as a community prevent rock stars?. Also see the talk Mamas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Rock Star Developers.

- What about Bob as a manager? Bob may seek and be offered promotions into management, and become even more damaging to the company. Bob the manager exploits and threatens his subordinates. That's a topic for another post.

- Does Bob sexually assault others? Is Bob more likely to be a harasser due to delusions of grandeur and a sense of entitlement (Al Capone theory), or is he smart enough not to go that far, or, is he simply not that kind of jerk? I don't know. That's outside of my firsthand experience, so I didn't include it.

- What about those junior engineers? The ones Bob exploits for his own gain. That's another big topic. Some related reading here, here, and here (from which I borrowed the words "reflecting glory").

- Is Bob actually brilliant? It's a little hard to tell, since Bob takes credit for the work of others. Bob also creates enemies in the industry, and some staff even sabotage Bob's work. In the long run, it hurts Bob's career. Not a brilliant result, really.

- What if Bob is pretending to be brilliant? (Updated) The consequences for the company can be worse. I didn't explore this topic here, but it would be a character similar to Bob who isn't actually brilliant, but pretends to be, and has most people believing him. To quote from a HN comment: "The myth of "brilliant jerks" is harmful because it lets any jerk pretend he's doing it because he's brilliant, when chances are he's just afraid of being unmasked as mediocre.".

- Does anyone exist who is really as bad as fictional Bob? Yes. Fortunately they are rare. One reviewer thinks that my post will not be effective unless I name such a real-life Bob as a concrete example. Maybe they are right, but I've avoided that here. This isn't about one Bob, it's about all selfish brilliant jerks.

- Should we publicly call out brilliant jerks in tech? It's a complex topic. The book Is Shame Necessary does make the point that shame and humiliation have a legitimate place in society when they are natural consequences to abusive behavior, which is also discussed in this post. Calling out abusers may save future victims of abuse, so long as the calling out is proportional and not abusive itself. For victims of abuse, I could not make a blanket recommendation: I don't know your specific situation and how safe it is for you to speak up. I've been in this situation myself, and was facing an extreme threat to myself and my family, and I understand how risky it can be.

- How do I know if I'm the jerk? If you always think that being right is all that matters, and don't consider your impact on teamwork or relationships, you might be an Alice or a Bob. If you think that hurting other people is simply doing what it takes to get ahead, then you might be a Bob. See the earlier sections for more characteristics, and my colleague's QCon presentation: Am I a Brilliant Jerk?

Conclusion

Should brilliant jerks be tolerated? To explore this, I described two fictional brilliant jerks: Alice, who is selfless, and Bob, who is selfish. This makes it clear that the behavior of selfish jerks, like Bob, should definitely not be tolerated. Bob can kill companies. When CEOs and VCs sometimes say that brilliant jerks may be worth it, I imagine they are thinking of Alice, a selfless jerk, and not Bob. (Alice is debatable.)

Early on in my career, I supported brilliant jerks of any type and thought they were worth it. I was wrong. People had warned me about them, that their behavior was "not ok," but they never went into much detail as to why. I've shared many details here. I didn't figure this all out until seeing the behavior and damage firsthand. (I've not only experienced it, but I may have reached my lifetime dosage of asshole-rads.)

Companies can adopt a "no asshole rule," or more politely, a "no brilliant jerks" policy. Colleagues may be genuinely conflicted about how to deal with Bob. On the one hand, he is a real jerk, but on the other he is a "high performer," so isn't it in the company's best interest to tolerate his behavior? A policy helps you decide, and it can be as simple as three words: no brilliant jerks.

Acknowledgements

Picture and editing by Deirdré Straughan. Thanks to review feedback and suggestions from Alice Goldfuss, Baron Schwartz, Ed Hunter, Justin Becker, David Blank-Edelman, Valerie Aurora, and others. References and related reading:

- Sutton, R. The No Asshole Rule. Grand Central Publishing, 2010.

- Babiak, P., Hare, R. D. Snakes in Suits. Harper Business, 2007.

- Jacquet, J. Is Shame Necessary. Random House, 2015.

- Sutton, R. The Asshole Survival Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

- https://hbr.org/2015/12/its-better-to-avoid-a-toxic-employee-than-hire-a-superstar

- https://retrospective.co/brilliant-jerks-cost-more-than-they-are-worth/

- http://boz.com/articles/be-kind.html

- https://hypatia.ca/2016/06/21/no-more-rock-stars/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awdVoPAU0Ic

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJOSX-W0yHA&feature=youtu.be&t=10m53s

- https://www.slideshare.net/reed2001/culture-1798664/36-Brilliant_Jerks_Some_companies_tolerate

- https://jobs.netflix.com/culture

- https://qconsf.com/sf2017/presentation/am-i-brilliant-jerk

- https://hypatia.ca/2017/07/18/the-al-capone-theory-of-sexual-harassment/

- The blood bag series: part 1, part 2, part 3

- (Updated) discussion on hackernews

Click here for Disqus comments (ad supported).